-

play_arrow

play_arrow

Clubalicious Clubalicious Radio

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

London Calling Podcast Yana Bolder

Dive into Part 2 of our look into how software developers simulate, re-create and emulate classic analog gear for modern workflows—but don’t pass up Part 1!

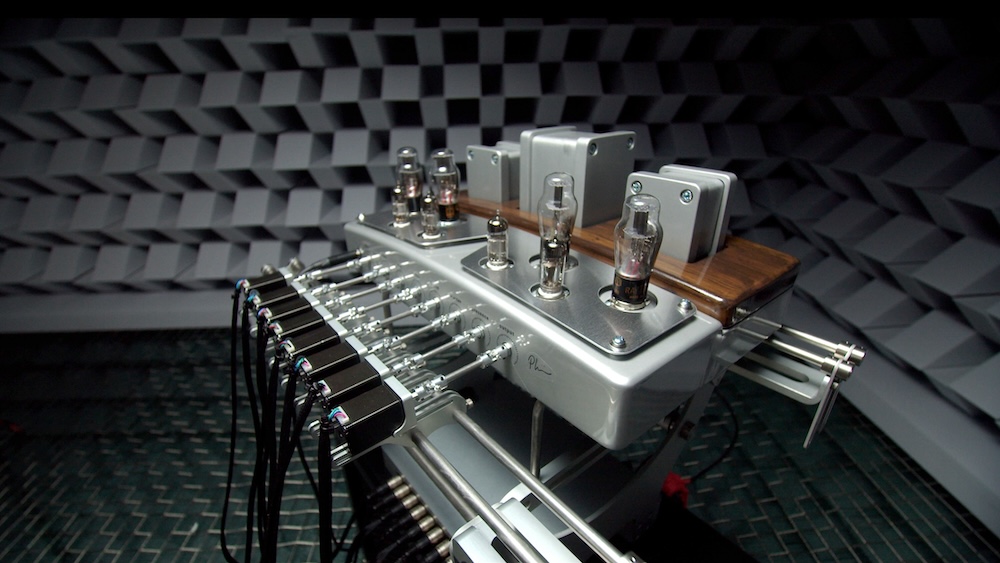

ROOMS, AMPS AND MICS

Depending on the type of hardware being modeled, several other techniques are often necessary in addition to those used for modeling a unit’s electronics. If speakers and/or room acoustics are part of the equation, as is the case with amp modeling and room simulation, developers might employ convolution, creating impulse responses (IRs) that describe the acoustics of a given space.

The limitation of an IR is that it’s a snapshot, so it’s a static representation of the sound in the space it was recorded. To add additional realism, Universal Audio developed a technology it calls Dynamic Room Modeling, which emulates how microphones are physically repositioned in a live room or reverb chamber.

Rosén says that Softube often uses a different type of convolution involving Infinite Impulse Responses (IIRs)—also known as recursive filters—in conjunction with conventional IRs for speaker modeling. “It’s much more CPU-efficient,” he explains. “IIRs are usually not is big analog EQs, because there are so many accurate enough on their own, but a useful tool in combination with other techniques.”

Microphones are yet another type of hardware that requires multiple techniques to emulate. Developers must factor in polar patterns, mic distance, distance of the source to the mic, off-axis response, and properties of the materials used in the mics. As a result, modeling a mic requires many additional physical measurements, convolution integration and, of course, a lot of math.

ABOVE AND BEYOND

Modeled plug-ins can claim an advantage (depending on your point of view) over the original units in that they have the ability to add features that are only possible in the digital domain. In the early days of modeling, developers often hesitated to make such additions because the goal was typically “absolute authenticity.”

“To this day, we are adamant about creating the models, warts and all,” Shanks says, “meaning with all the quirks and idiosyncrasies of the sound and the hardware experience. Basically, what you see is what you get. For example, our original 1176 plugin gave you exactly what the hardware provided; no bells and whistles such as parallel mix or sidechain filtering like the current versions.”

Now, he says, UA is more flexible in its viewpoint, and many of the company’s plug-ins include “digital only” features that expand the functionality. “For example, on Hitsville Mastering EQ, we added the ability to turn it into a mid-side EQ,” he notes. “That’s the kind of thing we don’t think impacts the unit’s integrity.”

Rosén says that Softube is also open to adding features that are not on the original hardware. “It would be stupid to say, ‘No, we will not put a stereo side-chain in this unit because the original was mono,’” he says. “Some things are very reasonable to add because you use the units differently in a digital workflow compared to analog.”

KIT Plugins has yet another philosophy. “John and I try to take an approach somewhere in the middle,” Kleinman explains. “We want to capture the magic of the original gear, and we both agree that one of the things that makes analog gear magical is its limitations, like on a 1073. You have to work within the limitations of that piece of gear, so you find a different way to get your answer. But at the same time, we are building a digital version of a product, and there are certain annoyances or problems in the real world that we want to fix. For example, analog noise. We include the noise in our plug-ins, but you can turn it on, control its volume, and turn it off to get pure digital silence when there’s no sound playing.”

LISTEN UP

Along with all the measuring, data collection and math, listening to the modeled processor compared to the original is a part of the digitalmodeling workflow that leans a bit more toward the artistic side.

“When I finally sit down after the first pass of the algorithm is complete, I’m side by side with a piece of hardware and my software, listening back and forth, doing signal analysis and spectrum analysis to see if it matches in every way,” Shanks says.

“There’s always A/B testing,” Rosén adds, “and that can be a long, tedious process. A/Bing is more difficult than you might think because there are so many factors that can screw up the test.”

At KIT, there is a simple yardstick for knowing whether a model passes muster: They do a blind A/B test with John McBride as the judge. “The threshold for us to release a piece of gear,” says Kleinman, “is that John has to be fooled in the blind test. When a studio professional with intimate knowledge of the modeled gear can’t distinguish its output from that of the plug-in, it’s safe to say that the modeling project has been a success.”

Written by: Admin

Similar posts

Recent Posts

- 🎶 New Music: JID, OneRepublic, Morgan Wallen, Post Malone, MarkCutz, Kidd Spin + More!

- Classic Tracks: The Fireballs’ “Sugar Shack”

- Classic Tracks: Arlo Guthrie’s “City of New Orleans”

- Classic Track: k.d. lang’s “Constant Craving”

- Classic Tracks: Waylon Jennings’ “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way”

Recent Comments

No comments to show.Featured post

Latest posts

🎶 New Music: JID, OneRepublic, Morgan Wallen, Post Malone, MarkCutz, Kidd Spin + More!

Classic Tracks: The Fireballs’ “Sugar Shack”

Classic Tracks: Arlo Guthrie’s “City of New Orleans”

Classic Track: k.d. lang’s “Constant Craving”

Classic Tracks: Waylon Jennings’ “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way”

Current show

Upcoming shows

Femme House

Lp giobbi

19:00 - 20:00

Stereo Productions

Chus Ceballos

20:00 - 21:00

Fresh Is Fresh

This Weeks Hottest Releases

21:00 - 00:00

Love To Be

The Global Connection

00:00 - 02:00

Fresh Is Fresh

This Weeks Hottest Releases

02:00 - 09:00Chart

Powered by Dee jay promotions visit us

Invalid license, for more info click here

Invalid license, for more info click here